MALARIA :

Malaria is a vector-borne infectious disease caused by a eukaryotic protist of the genus Plasmodium. It is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, including parts of the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Each year, there are approximately 350–500 million cases of malaria, killing between one and three million people, the majority of whom are young children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ninety percent of malaria-related deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria is commonly associated with poverty, but is also a cause of poverty and a major hindrance to economic development.

Malaria is one of the most common infectious diseases and an enormous public health problem. Five species of the plasmodium parasite can infect humans; the most serious forms of the disease are caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae causes milder disease in humans that is not generally fatal. A fifth species, Plasmodium knowlesi, causes malaria in macaques but can also infect humans. This group of human-pathogenic Plasmodium species is usually referred to as malaria parasites.

Usually, people get malaria by being bitten by an infective female Anopheles mosquito. Only Anopheles mosquitoes can transmit malaria, and they must have been infected through a previous blood meal taken on an infected person. When a mosquito bites an infected person, a small amount of blood is taken, which contains microscopic malaria parasites. About one week later, when the mosquito takes its next blood meal, these parasites mix with the mosquito's saliva and are injected into the person being bitten. The parasites multiply within red blood cells, causing symptoms that include symptoms of anemia (light-headedness, shortness of breath, tachycardia, etc.), as well as other general symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, flu-like illness, and, in severe cases, coma, and death. Malaria transmission can be reduced by preventing mosquito bites with mosquito nets and insect repellents, or by mosquito control measures such as spraying insecticides inside houses and draining standing water where mosquitoes lay their eggs. Work has been done on malaria vaccines with limited success and more exotic controls, such as genetic manipulation of mosquitoes to make them resistant to the parasite have also been considered.

Although some are under development, no vaccine is currently available for malaria that provides a high level of protection; preventive drugs must be taken continuously to reduce the risk of infection. These prophylactic drug treatments are often too expensive for most people living in endemic areas. Most adults from endemic areas have a degree of long-term infection, which tends to recur, and also possess partial immunity (resistance); the resistance reduces with time, and such adults may become susceptible to severe malaria if they have spent a significant amount of time in non-endemic areas. They are strongly recommended to take full precautions if they return to an endemic area. Malaria infections are treated through the use of antimalarial drugs, such as quinine or artemisinin derivatives. However, parasites have evolved to be resistant to many of these drugs. Therefore, in some areas of the world, only a few drugs remain as effective treatments for malaria.

Symptoms :

Symptoms of malaria include fever, shivering, arthralgia (joint pain), vomiting, anemia (caused by hemolysis), hemoglobinuria, retinal damage, and convulsions. The classic symptom of malaria is cyclical occurrence of sudden coldness followed by rigor and then fever and sweating lasting four to six hours, occurring every two days in P. vivax and P. ovale infections, while every three for P. malariae. P. falciparum can have recurrent fever every 36–48 hours or a less pronounced and almost continuous fever. For reasons that are poorly understood, but that may be related to high intracranial pressure, children with malaria frequently exhibit abnormal posturing, a sign indicating severe brain damage. Malaria has been found to cause cognitive impairments, especially in children. It causes widespread anemia during a period of rapid brain development and also direct brain damage. This neurologic damage results from cerebral malaria to which children are more vulnerable. Cerebral malaria is associated with retinal whitening,which may be a useful clinical sign in distinguishing it from other causes of fever.

Severe malaria is almost exclusively caused by P. falciparum infection and usually arises 6–14 days after infection. Consequences of severe malaria include coma and death if untreated—young children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable. Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), severe headache, cerebral ischemia, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), hypoglycemia, and hemoglobinuria with renal failure may occur. Renal failure may cause blackwater fever, where hemoglobin from lysed red blood cells leaks into the urine. Severe malaria can progress extremely rapidly and cause death within hours or days. In the most severe cases of the disease fatality rates can exceed 20%, even with intensive care and treatment. In endemic areas, treatment is often less satisfactory and the overall fatality rate for all cases of malaria can be as high as one in ten. Over the longer term, developmental impairments have been documented in children who have suffered episodes of severe malaria.

Chronic malaria is seen in both P. vivax and P. ovale, but not in P. falciparum. Here, the disease can relapse months or years after exposure, due to the presence of latent parasites in the liver. Describing a case of malaria as cured by observing the disappearance of parasites from the bloodstream can, therefore, be deceptive. The longest incubation period reported for a P. vivax infection is 30 years. Approximately one in five of P. vivax malaria cases in temperate areas involve overwintering by hypnozoites (i.e., relapses begin the year after the mosquito bite).

Causes :

Malaria parasites are members of the genus Plasmodium (phylum Apicomplexa). In humans malaria is caused by P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, P. vivax and P. knowlesi. P. falciparum is the most common cause of infection and is responsible for about 80% of all malaria cases, and is also responsible for about 90% of the deaths from malaria. Parasitic Plasmodium species also infect birds, reptiles, monkeys, chimpanzees and rodents. There have been documented human infections with several simian species of malaria, namely P. knowlesi, P. inui, P. cynomolgi, P. simiovale, P. brazilianum, P. schwetzi and P. simium; however, with the exception of P. knowlesi, these are mostly of limited public health importance.Although avian malaria can kill chickens and turkeys, this disease does not cause serious economic losses to poultry farmers. However, since being accidentally introduced by humans it has decimated the endemic birds of Hawaii, which evolved in its absence and lack any resistance to it.

Vaccination :

Immunity (or, more accurately, tolerance) does occur naturally, but only in response to repeated infection with multiple strains of malaria.

Vaccines for malaria are under development, with no completely effective vaccine yet available. The first promising studies demonstrating the potential for a malaria vaccine were performed in 1967 by immunizing mice with live, radiation-attenuated sporozoites, providing protection to about 60% of the mice upon subsequent injection with normal, viable sporozoites. Since the 1970s, there has been a considerable effort to develop similar vaccination strategies within humans. It was determined that an individual can be protected from a P. falciparum infection if they receive over 1,000 bites from infected, irradiated mosquitoes.

It has been generally accepted that it is impractical to provide at-risk individuals with this vaccination strategy, but that has been recently challenged with work being done by Dr. Stephen Hoffman, one of the key researchers who originally sequenced the genome of Plasmodium falciparum. His work most recently has revolved around solving the logistical problem of isolating and preparing the parasites equivalent to 1000 irradiated mosquitoes for mass storage and inoculation of human beings. The company has recently received several multi-million dollar grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.S. government to begin early clinical studies in 2007 and 2008. The Seattle Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI), funded by the Malaria Vaccine Initiative, assures potential volunteers that "the [2009] clinical trials won't be a life-threatening experience. While many volunteers [in Seattle] will actually contract malaria, the cloned strain used in the experiments can be quickly cured, and does not cause a recurring form of the disease." "Some participants will get experimental drugs or vaccines, while others will get placebo."

Instead, much work has been performed to try and understand the immunological processes that provide protection after immunization with irradiated sporozoites. After the mouse vaccination study in 1967, it was hypothesized that the injected sporozoites themselves were being recognized by the immune system, which was in turn creating antibodies against the parasite. It was determined that the immune system was creating antibodies against the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) which coated the sporozoite. Moreover, antibodies against CSP prevented the sporozoite from invading hepatocytes. CSP was therefore chosen as the most promising protein on which to develop a vaccine against the malaria sporozoite. It is for these historical reasons that vaccines based on CSP are the most numerous of all malaria vaccines.

Presently, there is a huge variety of vaccine candidates on the table. Pre-erythrocytic vaccines (vaccines that target the parasite before it reaches the blood), in particular vaccines based on CSP, make up the largest group of research for the malaria vaccine. Other vaccine candidates include: those that seek to induce immunity to the blood stages of the infection; those that seek to avoid more severe pathologies of malaria by preventing adherence of the parasite to blood venules and placenta; and transmission-blocking vaccines that would stop the development of the parasite in the mosquito right after the mosquito has taken a bloodmeal from an infected person. It is hoped that the sequencing of the P. falciparum genome will provide targets for new drugs or vaccines.

The first vaccine developed that has undergone field trials, is the SPf66, developed by Manuel Elkin Patarroyo in 1987. It presents a combination of antigens from the sporozoite (using CS repeats) and merozoite parasites. During phase I trials a 75% efficacy rate was demonstrated and the vaccine appeared to be well tolerated by subjects and immunogenic. The phase IIb and III trials were less promising, with the efficacy falling to between 38.8% and 60.2%. A trial was carried out in Tanzania in 1993 demonstrating the efficacy to be 31% after a years follow up, however the most recent (though controversial) study in The Gambia did not show any effect. Despite the relatively long trial periods and the number of studies carried out, it is still not known how the SPf66 vaccine confers immunity; it therefore remains an unlikely solution to malaria. The CSP was the next vaccine developed that initially appeared promising enough to undergo trials. It is also based on the circumsporoziote protein, but additionally has the recombinant (Asn-Ala-Pro15Asn-Val-Asp-Pro)2-Leu-Arg(R32LR) protein covalently bound to a purified Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin (A9). However at an early stage a complete lack of protective immunity was demonstrated in those inoculated. The study group used in Kenya had an 82% incidence of parasitaemia whilst the control group only had an 89% incidence. The vaccine intended to cause an increased T-lymphocyte response in those exposed, this was also not observed.

The efficacy of Patarroyo's vaccine has been disputed with some US scientists concluding in The Lancet (1997) that "the vaccine was not effective and should be dropped" while the Colombian accused them of "arrogance" putting down their assertions to the fact that he came from a developing country.

The RTS,S/AS02A vaccine is the candidate furthest along in vaccine trials. It is being developed by a partnership between the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative (a grantee of the Gates Foundation), the pharmaceutical company, GlaxoSmithKline, and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research In the vaccine, a portion of CSP has been fused to the immunogenic "S antigen" of the hepatitis B virus; this recombinant protein is injected alongside the potent AS02A adjuvant. In October 2004, the RTS,S/AS02A researchers announced results of a Phase IIb trial, indicating the vaccine reduced infection risk by approximately 30% and severity of infection by over 50%. The study looked at over 2,000 Mozambican children. More recent testing of the RTS,S/AS02A vaccine has focused on the safety and efficacy of administering it earlier in infancy: In October 2007, the researchers announced results of a phase I/IIb trial conducted on 214 Mozambican infants between the ages of 10 and 18 months in which the full three-dose course of the vaccine led to a 62% reduction of infection with no serious side-effects save some pain at the point of injection. Further research will delay this vaccine from commercial release until around 2011

Treatment :

Active malaria infection with P. falciparum is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization. Infection with P. vivax, P. ovale or P. malariae can often be treated on an outpatient basis. Treatment of malaria involves supportive measures as well as specific antimalarial drugs. When properly treated, someone with malaria can expect a complete recovery

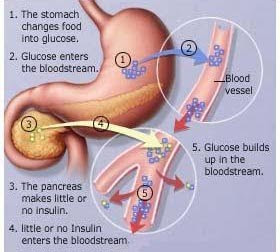

A chronic condition that results from deficiencies in the body's ability to produce or use insulin, which is a substance that keeps blood sugar levels stable.

A chronic condition that results from deficiencies in the body's ability to produce or use insulin, which is a substance that keeps blood sugar levels stable.